Why AI is going nuclear

Join our daily and weekly newsletters for the latest updates and exclusive content on industry-leading AI coverage. Learn More

If you’re of a certain age, the words “nuclear energy” probably conjure up dystopian images of power plants melting down, glowing radioactive waste, protesters, and other dark scenes ranging from the unfortunate to apocalyptic.

The truth is, nuclear power’s reputation has been mostly unfairly blemished since 1970s and ’80s thanks to the Three Mile Island and Chernobyl meltdowns in Pennsylvania and Ukraine (at that time, part of the Soviet Union), respectively. While terrible, these disasters belie nuclear energy’s true safety record, which is actually much better for humans and of course, the environment, than most other power sources — even renewables, and even accounting for the fact that nuclear waste needs to go somewhere.

Now in the year 2024, some of the largest technology companies on Earth are ready to embrace nuclear power again — and the reason is because of artificial intelligence (AI).

Which companies are embracing nuclear to power AI operations?

Looking over the last 9-10 months, and in particular, the last few weeks, Microsoft, Google, and Amazon have all announced large-scale commitments to buy, invest in, and/or help build new nuclear power plants. It’s no coincidence these rivals are the three top providers of cloud computing and cloud storage solutions in the world, and have also been among the biggest to embrace and provide AI models and technology to customers, both other businesses and end-users.

Specifically, the major AI-nuclear projects that have been announced this year include:

- Google has partnered with Kairos Power to utilize small modular reactors (SMRs) to power its AI data centers. The deal is projected to deliver 500 megawatts of carbon-free power by 2035, as part of Google’s broader goal of operating on 24/7 carbon-free energy by 2030. These advanced reactors offer a simplified and safer design, aligning with Google’s push for sustainability.

- Microsoft has agreed to restart the dormant Three Mile Island reactor in Pennsylvania by 2028 through a partnership with Constellation Energy. This plant will provide 835 megawatts of power, supporting Microsoft’s data centers as AI energy consumption continues to rise. Additionally, Microsoft has signed a contract with Helion Energy to explore fusion energy, positioning it as a potential future energy source. Earlier this year, The Information reported that Microsoft and OpenAI were reportedly partnering on a $100 billion AI supercomputer codenamed “Stargate” that would require 5 gigawatts (5000 megawatts to power), or just under the amount of power consumed regularly by New York City (all for one computer!!)

- Amazon announced on October 16, 2024, that it signed three new agreements to support nuclear energy development through SMRs. In Washington, Amazon is working with Energy Northwest to develop four SMRs, projected to generate 320 megawatts in the first phase, with the potential to increase to 960 megawatts. The project is expected to begin powering the Pacific Northwest in the 2030s. Amazon is further partnering with X-energy, which will supply the SMR technology, enabling future projects to develop more than five gigawatts of nuclear power. Furthermore, Amazon is exploring SMR development with Dominion Energy in Virginia, adding at least 300 megawatts to meet the region’s growing demand. Amazon’s existing deal with Talen Energy involves a $650 million investment in a Pennsylvania data center powered directly by nuclear energy, helping preserve an older reactor and creating jobs.

SMRs, as mentioned in several of the deals above, are reactors with a maximum output of 300 MWe, producing 7.2 million kWh per day.

They are smaller than traditional reactors, which exceed 1,000 MWe, and offer greater flexibility due to their modular design, allowing for production and assembly in factories rather than on the site of the actual power station itself.

They’re cooled by light water, liquid metal, or molten salt and incorporate passive safety systems, utilizing natural circulation for core cooling and reducing the need for operator intervention, which simplifies design and minimizes failure risks.

What’s driving the move to nuclear?

Clearly, the major cloud-turned AI model providers see an enormous future for nuclear power behind their operations.

But why and why now? To find out, I reached out to Edward Kee, CEO and founder of Nuclear Economics Consulting Group, a nuclear energy consulting firm, who previously worked as a merchant power plant developer and a nuclear power plant engineer for U.S. Navy Nimitz-class aircraft carriers.

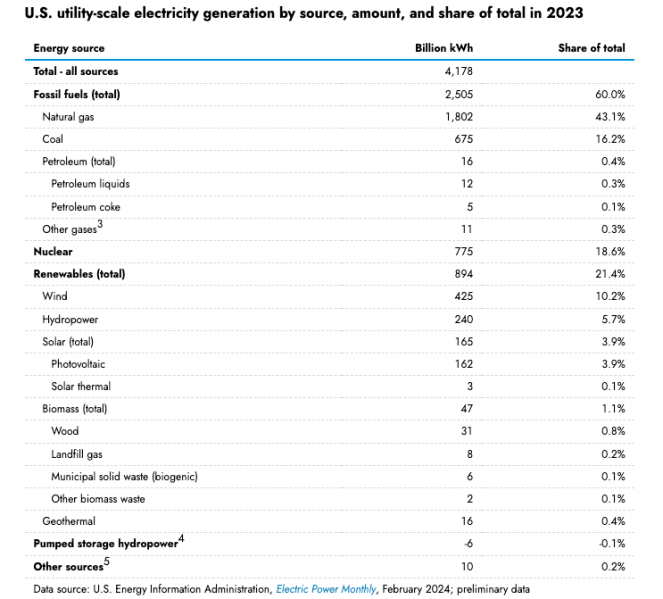

According to Kee — who of course, is incentivized to see more nuclear power spin up — the answer is that data centers used to train and serve up inferences of AI models to customers require a lot of energy, and right now, the only way to deliver it is largely through a fossil fuel-powered electrical grid, which will impede the tech companies from achieving their climate and emissions goals.

“The value of clean, reliable electricity for these data centers is pretty high,” he told me in a videoconference interview earlier this week. “Most companies have committed to zero-carbon power by 2030 or 2035, but using renewable energy accounting methods is a bit fallacious because solar doesn’t work at night, and wind doesn’t work when there’s no wind.”

Indeed, AI is a particularly power intensive industry. As Anna-Sofia Lesiv wrote for the venture capital firm Contrary last summer:

“Training foundational AI models can be quite energy-intensive. GPT-3, OpenAI’s 175 billion parameter model, reportedly used 1,287 MWh to train, while DeepMind’s 280 billion parameter model used 1,066 MWh. This is about 100 times the energy used by the average US household in a year.”

And as the International Atomic Energy Agency (IAEA), a non-profit international research and standards body dedicated to nuclear energy, wrote in a report released just this week:

“As electricity consumption by data centers, cryptocurrencies and artificial intelligence companies is expected to double from 2022 to 2026, these companies are seeking the next generation of clean energy technologies that can help to meet their goals.“

Driven in part by this increasing demand from the tech sector, IAEA issued a high-end projection in the report that finds a 150% increase in global nuclear generation capacity to 950 gigawatts by 2050.

However, the IAEA cautions this high-end projection will require a $100 billion investment over the same 25-year timeframe — “a fraction of what the world invests in energy infrastructure overall, but a big change from the level of investment in nuclear over the past 20 years.”

Tech companies are trying to thread a commercial and political needle to get the power they need

While one might think that tech companies of all entities would have no trouble obtaining power from the existing electrical grid (powered mainly by natural gas and coal in the U.S.), the reality according to Kee is that municipal and private power utilities companies are wary of committing a significant portion of their output to new data centers, which could strain their ability to serve their current crop of residential and commercial customers beyond tech.

The tech companies are “talking about adding frankly enormous amounts of new demand in terms of gigawatts on the grid,” the nuclear expert told VentureBeat. “And increasingly, the states and the utilities where they’re going to put those data centers are saying, ‘Hold on a minute, guys. You can’t just show up here and connect and take hundreds of megawatts or gigawatts of power without us having a plan to supply the generation to meet that demand. It’s going to cause problems.’”

Therefore, in order to even get approval for new data center projects and large AI training “superclusters” of graphics processing units (GPUs) from Nvidia and others — like the kind Elon Musk’s xAI just turned on in Memphis, Tennessee — municipal and state lawmakers and regulatory agencies may be asking the tech companies to come up with a plan for how they will be powered without draining too much from the existing grid.

“Talking a lot about your nuclear plants could help you with that in terms of public perception,” Kee said.

Why having nuclear power located physically and geographically beside data centers is so appealing

You might also think that tech companies looking to nuclear to solve their AI energetic problems would be happy getting power from any nuclear plant, even ones far away from where their data centers would be situated.

But even though we consumers often think of the “cloud” on which many AI servers run as some sort of ethereal, nonphysical space of electrons floating above us or around us and that we dip into and out of with our devices as needed, the fact is it is still enabled by physical metal and silicon computer chips and hardware, and as such, its performance is subject to the same physics as the rest of the world.

Therefore, putting data centers as close as possible to their power sources — in this case, nuclear power plants — is advantageous to the companies.

“We think of this AC power network we have as being pretty much fungible so you can get power at one point and customers another point,” Kee explained. “But when you have huge hundred megawatt gigawatt scale loads, you’re going to have to upgrade and change your transmission system which means a building new transmission lines.”

Instead of doing that, the big tech companies would be better off situating servers right beside the power generation facility itself, avoiding the cost of building more infrastructure to carry the vast energy loads they require.

What does big tech’s sudden interest in nuclear mean for the long run?

Ever the techno optimist, I personally couldn’t help but get a little wide eyed at the recent announcements of Amazon, Google, and Microsoft putting money towards new nuclear plants.

I myself have gone on a journey of being wary about nuclear power to being more open to it in order to help reduce emissions for the sake of our climate and environment — much like the environmentalist advocacy nonprofit group the Sierra Club (founded by former Bay Area prominent resident John Muir), which recently endorsed nuclear power to the surprise of many given its long history of opposition.

A future where powerful AI models help increase the demand for, and maybe even optimize the safety and performance of new nuclear power plants sounds awesome and compelling to me. If AI is what it takes the world to look again at nuclear and embrace it as one of the major sources of clean energy, so be it. Could AI usher in a nuclear energy renaissance?

Kee, for his part, is less certain about that optimistic worldview, noting that whether building new small modular nuclear reactors (SMRs) or restarting old full scale power plants like Three Mile Island, the U.S. federal government through the agency the Nuclear Regulatory Commission will still need to review and approval all the projects, which is likely to take several years at the earliest.

“Some of these announcements may be a bit hyperbolic in there on their promises and expectations,” he told VentureBeat. “So you want to keep your seatbelt on for a while.”

Still, having been working in the nuclear sector for decades now, Kee is encouraged by big tech’s lofty promises and does believe it could spur new nuclear energy investment more generally.

“There’s been excitement around small and advanced reactors for a decade or more, and now it’s linking up with the big technology power demand world…That’s kind of cool,” he told VentureBeat. “I don’t know which other sectors might follow, but you’re right—it could happen. If some of these new reactor designs get built, which was always in doubt because the economics are questionable for the first one, it might become easier to build a whole fleet by other parties, including utilities or municipalities.”

Source link