Inside the fight to ban — and destroy — PFAS ‘forever chemicals’

For over 40 years, Ted Van der Vlies and his wife Marga grew fruits and vegetables in their backyard on the outskirts of Dordrecht, the Netherlands. Onions, potatoes, lettuce, carrots, rhubarb, cherries, you name it.

Little did they know that their homegrown produce was likely poisoning them.

Just a kilometre away from their garden sits the tangled mesh of steel pipes, giant vats, and smokestacks of the Chemours chemical plant. A recent court case found that the American conglomerate knowingly dumped PFAS chemicals into the environment around Dordrecht for decades.

Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances, or PFAS for short, are a group of more than 10,000 man-made chemicals famed for their water, heat, and oil resistant properties. They are found in thousands of products, from microchips and firefighting foam to food packaging and non-stick cookware.

While extremely useful, PFAS take thousands of years to break down in nature — lending them the name “forever chemicals.” Researchers have linked PFAS to decreased fertility, birth defects, and a multitude of cancers.

The levels of PFAS in Van der Vlies’ blood are dozens of times above the safety standard, Dutch documentary producer Zembla reports. He is seriously ill. He has both skin cancer and chronic leukaemia. Van der Vlies is adamant his condition was the result of drinking water and eating vegetables contaminated with the forever chemicals.

Public and regulatory legal pressure to phase out PFAS production is mounting.

Citizens are more aware of the issue than ever before. EU politicians from five member states have proposed a total ban on PFAS. Even major investors are urging chemical companies to clean up their act.

This has opened a new market for safer alternatives, as well as technologies to clean up the pollution already out there.

Yet, PFAS manufacturers and their industrial customers are pushing back. They argue that the chemicals are critical to the green transition and that a ban would reduce European competitiveness.

But do we really have to choose between fighting climate change or eliminating cancer-causing PFAS?

Destroying forever chemicals, forever

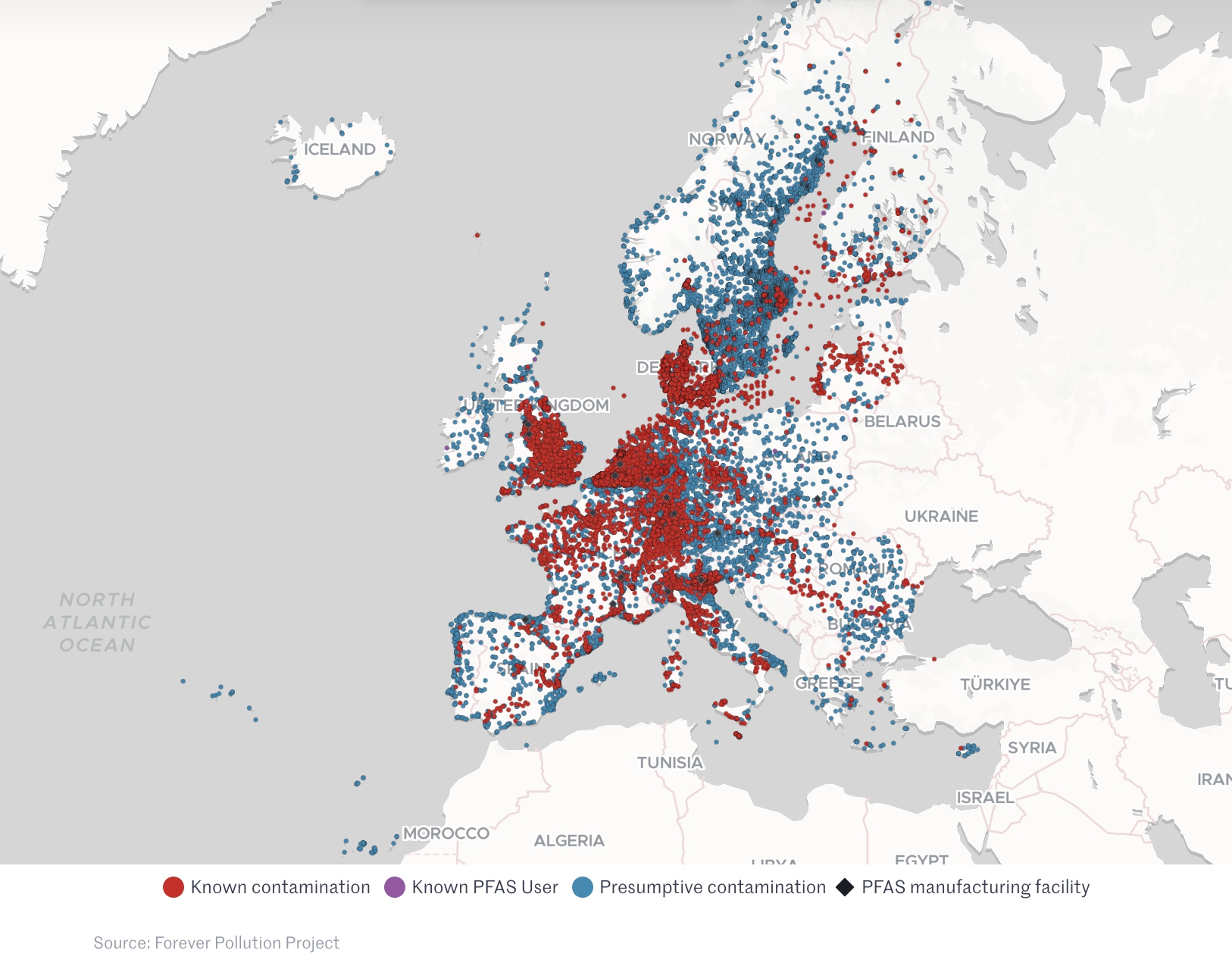

A recent cross-border investigation identified 17,000 sites across Europe polluted with PFAS. Of these, over 2,000 had levels of the chemicals that far exceeded the limit considered safe for humans.

There are a range of carbon and resin water filters that remove PFAS from water. Most water treatment facilities already use these filters in a process called reverse osmosis. But they’re far from 100% effective. Nor do they destroy the compounds.

Incineration was long considered the only way to break down PFAS permanently. However, it is energy intensive and studies have shown that it may just disperse the chemicals into the air instead.

“There are very few methods that we know of that permanently and safely destroy PFAS,” says Dr. Fajer Mushtaq, nanotechnology engineer and co-founder of Oxyle. “But it can be done.”

Oxyle is one of a small but rapidly growing cohort of companies working in PFAS remediation, a job that could cost $200 billion.

The Swiss company has developed a reactor that mineralises PFAS, breaking apart their carbon-fluorine bonds — one of the strongest in organic chemistry. Oxyle’s system doesn’t rely on heat to destroy the chemicals, which means its device uses far less energy than competitors’, says Mushtaq.

Key to the reaction is a so-called nanoporous catalyst. Mushtaq spent over 10 years developing this novel material during her time as a researcher at ETH Zurich.

The machine sucks up contaminated water into a chamber where it comes in contact with the catalyst. The reactor then vibrates, bubbles, and lights up the water. This motion activates the catalyst, which converts the energy into potent chemical “radicals.”

These highly reactive, electrically charged molecules oxidise anything in their path, including PFAS. Only minerals and water remain. This solution can be safely discharged back into the water supply.

Oxyle’s device uses machine learning algorithms to sieve through data from built-in sensors. This tells users what types of contaminants are in the water and whether they are above or below the mandated limits.

The startup recently completed a large-scale PFAS clean-up project for a chemical company in Switzerland. It pumped groundwater to the surface, treated it, and then put it back underground. Oxyle successfully eradicated 99% of PFAS from the site.

“We’re pretty much the only company in Europe doing this [PFAS destruction],” says Mushtaq. “But more and more are popping up, especially in the US. The potential for growth is huge.”

Washington-based Aquagga is another startup taking aim at PFAS. It has developed what it calls a “pressure cooker on steroids.” The device subjects water to extremely high temperatures and pressure, in an alkaline environment. The process completely breaks down the PFAS molecules.

The US Environmental Protection Agency (EPA) recently passed the world’s strictest requirements for PFAS levels in water. The law is expected to open the market for companies like Oxyle and Aquagga.

Meanwhile, Denmark, Germany, the Netherlands, Norway, and Sweden put forward a proposal last year for an EU-wide ban on all PFAS compounds. The European Chemicals Agency called it “one of the broadest restriction proposals in EU history.”

Pressure mounts

Incoming regulation isn’t just driving clean-up efforts, it’s targeting the problem at its source — PFAS production. And lawmakers aren’t the only ones calling on chemical companies to clean up their act.

In November, more than 50 investment firms representing $10 trillion in assets wrote to the world’s biggest producers of PFAS. They demanded that these companies phase out production, increase transparency, and invest in safer alternatives under the Investor Initiative on Hazardous Chemicals (IIHC).

“Chemical companies are used to dealing with complaints from NGOs and environmental groups, but when investors and politicians start applying pressure — that’s much more powerful,” says Jonatan Kleimark, senior chemicals and business advisor at ChemSec, a non-profit partly funded by the Swedish government. ChemSec advocates for stricter regulation of toxic chemicals.

Victims alleging harm from PFAS have lodged almost 10,000 lawsuits since 1999, according to a report. American chemical giant 3M, which invented the first PFAS almost a hundred years ago, recently agreed to settle one such claim for a whopping $10.5 billion.

“PFAS matters to investors because of the very direct impact on shareholder value from the increasing tide of litigation and regulation against chemical companies,” explains Eugenie Mathieu, earth lead at Aviva Investors.

3M shocked the world in 2022 when it committed to stop making PFAS by the end of 2025, citing pressure from regulators and investors.

But 3M is more the expectation than the rule — most big players are digging their heels in.

One of them is Chemours. The firm is one of the world’s largest PFAS producers, and the biggest supplier of fluoropolymers (a hard plastic type of PFAS) to the chip industry. Chemours is still investing heavily in PFAS production.

‘Critical to decarbonisation’

“In many critical applications there are no alternative materials that provide the unique and essential characteristics that fluoropolymers provide,” a Chemours spokesperson tells TNW. “The products we produce are critical to many advances in clean energy and decarbonisation.”

The company’s sentiment is echoed by many PFAS suppliers and their industrial customers, including the likes of TSMC and Intel — and it carries weight.

Aside from consumer products, PFAS are used in a number of technologies key to the green transition, from lithium-ion batteries to hydrogen fuel cells.

In chipmaking, PFAS products perform various key functions, for example, in the lithography manufacturing process. Nvidia — the chipmaker that’s ridden the AI hype wave to become one of the world’s most valuable companies — uses fluoropolymers in its semiconductors.

Makers and users of PFAS have formed a lobby group to fight against the EU ban. The companies are concerned that a broad restriction may lead to “disruptions of certain value chains” and “eventually eliminate some key applications,” a spokesperson for the group told Reuters.

Major PFAS manufacturers like Chemours and BASF also argue that a broad ban would not account for differences between the thousands of PFAS variants.

PFAS can be a solid, a liquid, or a gas. Some, like PFOA and PFOS, have been found to be especially dangerous.

“Lumping them all together doesn’t speak to the risks posed by a specific PFAS nor its uses and benefits,” says the Chemours spokesperson. “Essentially, it would be like regulating olive oil the same as motor oil because they are both hydrocarbons.”

The case for broad restriction

The EU has banned PFAS before. In 2020, the bloc prohibited the manufacture and sale of products containing PFOA — the chemical found in Van der Vlies’ blood.

Following the restriction, Chemours replaced the chemical, marketed as C8, with another PFAS it had developed years earlier: GenX. This new variant has since been linked to liver cancer.

“If you ban one they just create another,” says Dr Juliane Glüge, senior researcher in environmental chemistry at ETH Zurich.

All PFAS are persistent and accumulate in the environment and living things. Glüge and other scientists argue that this fact alone should be enough to justify a sweeping prohibition of all of the compounds.

Kleimark from Chemsec believes chemical companies are being “overly dramatic” in their claims that phasing out PFAS will stall the green transition.

“The vast majority of PFAS are not going toward critical applications,” he says. “And the proposed EU restriction makes concessions for specific use cases that don’t have viable alternatives, giving industry time to innovate new solutions.”

Finding and scaling PFAS alternatives

Alternatives to PFAS already exist for products like rain jackets, food-packaging, lubricants, and f-gases — used as coolants in air conditioning equipment and EV batteries.

For instance, Swedish chemical company OrganoClick has invented an alternative to PTFE, a PFAS commonly used in water-repellant clothing. Dubbed OrganoTex, the biomaterial mimics the properties of lotus leaves, which naturally repel water.

In the Netherlands, Eindhoven University of Technology spinout Solarge has made a PFAS-free solar panel.

But it’s not just early-stage companies working on solutions.

Japanese ink producer DIC has developed new PFAS-free surfactants for semiconductors. Mitsubishi Corp. has invented a hard-to-burn plastic material that can replace fluoropolymers in smartphones and laptops.

For cases where alternatives simply aren’t available, “we need to rapidly scale up research and development,” says Kleimark. Chemsec works with PFAS manufacturers to explore ways to scale safer alternatives.

As regulation tightens, litigation piles up, and investors apply pressure, the writing on the wall is getting bolder for PFAS manufacturers: start finding alternatives now or risk getting left behind.

A long road ahead

The EU’s PFAS restriction proposal could come into effect as early as 2026. It would also restrict the import of products containing the chemicals into the bloc.

However, whether the EU’s PFAS restriction proposal will come into force is still uncertain.

The chemical industry has been shown to use several strategies in the past — similar to those deployed by tobacco, pharmaceutical, and other industries — to influence science and regulation.

EU states may also be unwilling to make any move that could harm their competitiveness. This is especially true as the bloc looks to cut its reliance on foreign imports of key technologies.

“There’s a risk that the EU-wide ban will be watered down,” says Kleimark.

In the meantime, PFAS production continues pretty much unabated. An issue that was largely avoidable has now become “the greatest chemical threat facing humankind in the 21st Century,” to quote Dr Patrick Byrne from Liverpool John Moores University.

What’s clear is that the green transition should not justify continued PFAS production. Nor does one negate the other. Safe alternatives are out there — we just need to scale them up.

If there’s one thing PFAS manufacturers can teach us is that where there’s a will there’s a way. Now we can only hope the chemical industry dedicates as much energy toward solving the PFAS problem as it did toward covering it up.