140-year-old ocean heat tech could supply islands with limitless energy

A UK-based startup is looking to breathe new life into a century-old technology that could power tropical island nations with virtually limitless, consistent, renewable energy.

Known as ocean thermal energy conversion or ‘OTEC,’ the technology was first invented in 1881 by French physicist Jacques Arsene d’Arsonval. He discovered that the temperature difference between sun-warmed surface water and the cold depths of the ocean could be harnessed to generate electricity.

OTEC systems transfer heat from warm surface waters to evaporate a low-boiling point fluid like ammonia, creating steam that drives a turbine to produce electricity. As the vapour cools and condenses in contact with cold seawater pumped from the ocean’s depths, it completes the energy cycle.

How it works:

In theory, OTEC has the potential to produce at least 2,000GW globally, rivalling the combined capacity of all the world’s coal power plants. And unlike many renewables, it is a baseload source of power, which means it can run 24/7 with no fluctuation in output.

However, technological barriers, a lack of funding, and the meteoric rise of cheaper forms of renewable energy have largely pushed OTEC to the wayside. Globally, only two small demonstration plants are currently feeding energy to the grid — a 100kW one in Hawaii and another similarly-sized facility in Japan. That’s only enough energy for a hundred or so households.

Pipe problems

For OTEC to work it requires a temperature difference between hot and cold water of around 20 degrees Celsius. This can only be found in the tropics, which is not a problem in itself.

The real caveat is that an OTEC plant needs a constant supply of vast quantities of cold water from around 1,000m beneath the surface to operate efficiently. This means building a monumentally huge, storm-proof metal pipe of the kind that is, simply put, bloody expensive. For instance, just to scale up the current onshore plant in Kumejima, Japan to 1MW, the pipe alone could cost between $60mn and $80mn.

Yet, one startup based out of the UK remains undeterred by these seemingly insurmountable cost barriers. For aptly named Global OTEC, the time has come for an ocean energy renaissance.

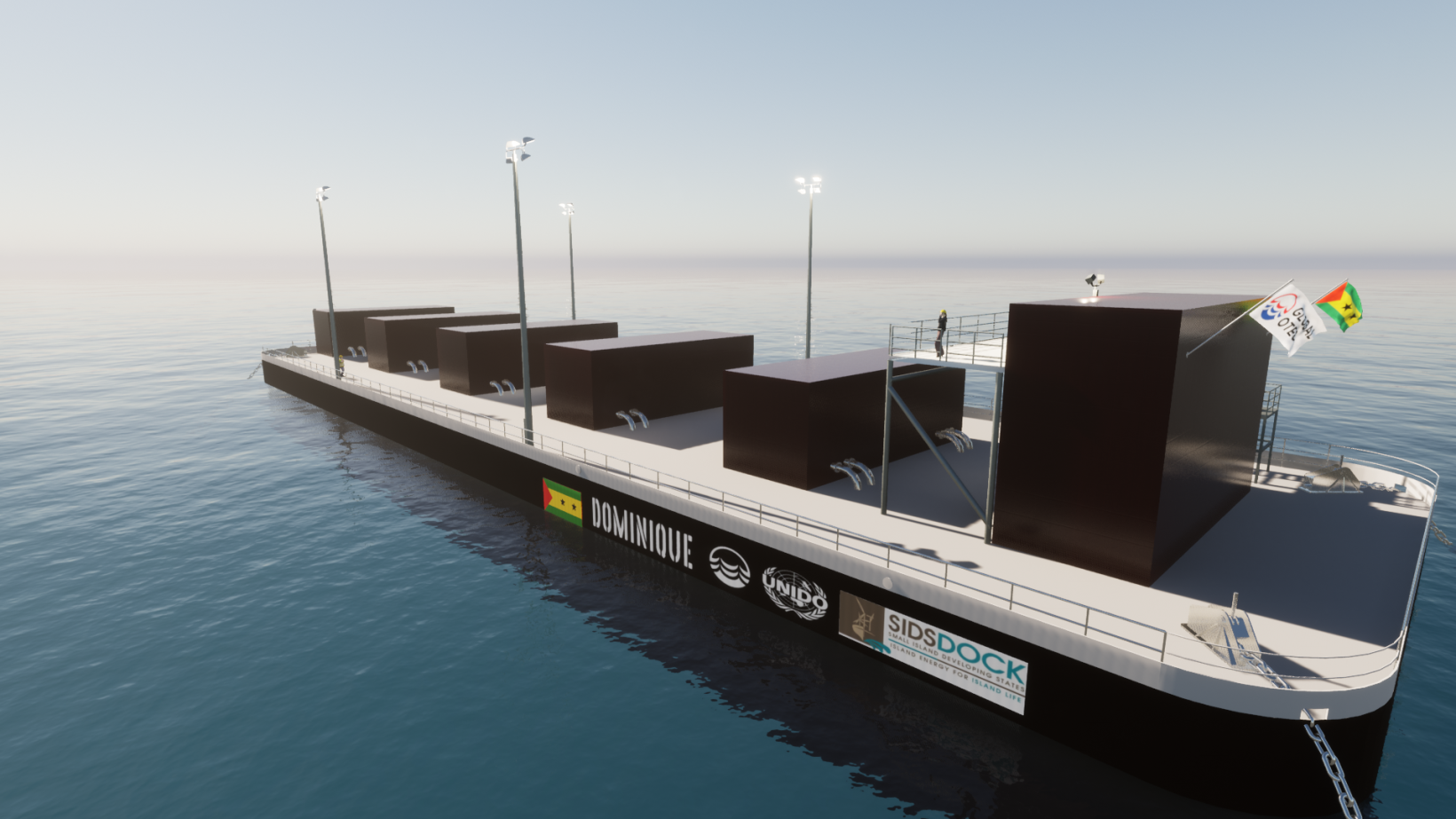

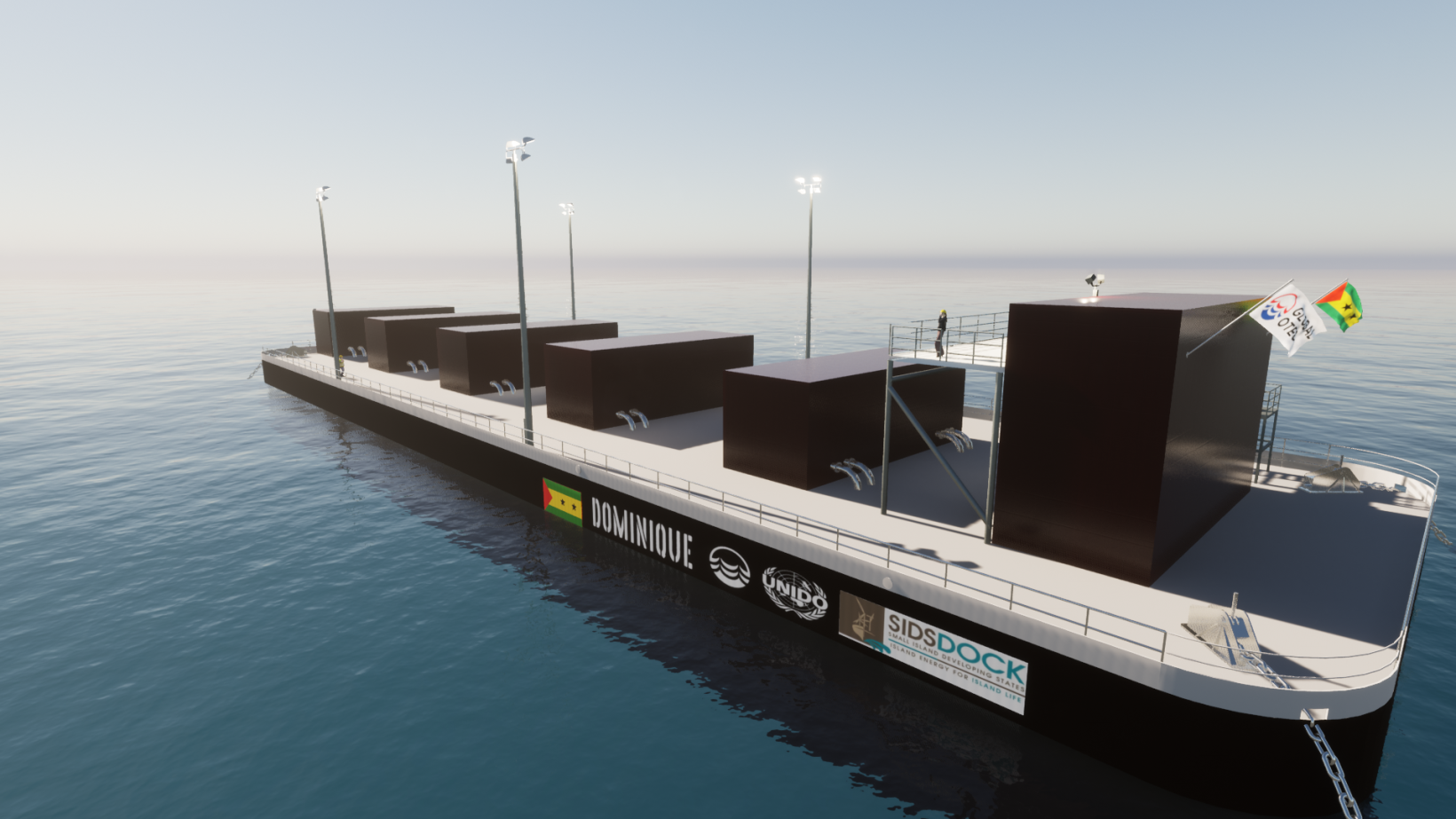

The company is developing a commercial-scale OTEC offshore rig that is specifically aimed at weaning small island nations off diesel fuel and onto clean, baseload energy. Named Dominique, the structure is designed to be modular and much cheaper than previous prototypes.

Learning from past mistakes

Global OTEC chose a floating barge design because onshore OTEC plants “require several multi-kilometre pipes fixed to the seabed” to facilitate the acquisition and safe discharge of water. This is partly why the Kumejima plant’s pipe costs are so astronomical.

Offshore rigs on the other hand just require one large cold-water pipe travelling straight down into the ocean’s depths — cutting costs. Global OTEC’s CEO and founder Dan Grech told TNW he estimates its cold-water pipe, which is around 750 metres long, will cost between $2.5-3mn to build.

“History is an important teacher, and we are committed to learning from it,” said Grech. “Failure of previous OTEC projects highlights where we should exercise caution,” he said. In June, the company gained a key design certification for the structure’s cold-pipe technology, an important step towards viability.

Tropical islands are largely dependent on imported fossil fuels, but with their wealth of sunshine, wind, and waves have huge renewable energy potential. For Grech, ocean thermal energy tech is ideally suited to supplying these island nations with baseload energy, alongside cheaper, but more intermittent renewables like wind and solar.

While Global OTEC is confident of its approach, the technology is still largely unproven on this scale. And as of the time of writing it remains uncertain as to where exactly the money for the Dominique installation will come from. Yet, with climate change accelerating — and island nations being among the most vulnerable to its impacts — attempting to harness the ocean’s heat on a commercial scale is surely, at the very least, worth a shot.